Meral Akkent

#DeBeje (#SpeakUp) – An Exhibition Experience

Museums are political spaces where power and identity are shaped. Like a family album, they seek to answer the question, “Who are we?” What is exhibited or left out is closely tied to power dynamics. Museums also influence and shape our perceptions of gender. Women’s and gender museums have been offering alternative concepts that challenge traditional museum approaches for over 40 years. Emerging alongside feminist debates in the 1980s, these alternative institutions create new spaces for Reflection and implementation in the contexts of representation, remembrance, and visibility.

The Istanbul Gender Museum is one of the institutions working in this field. With an inclusive, participatory, and intersectional approach, it designs and implements new methods for representation, remembrance, and visibility in its exhibitions.

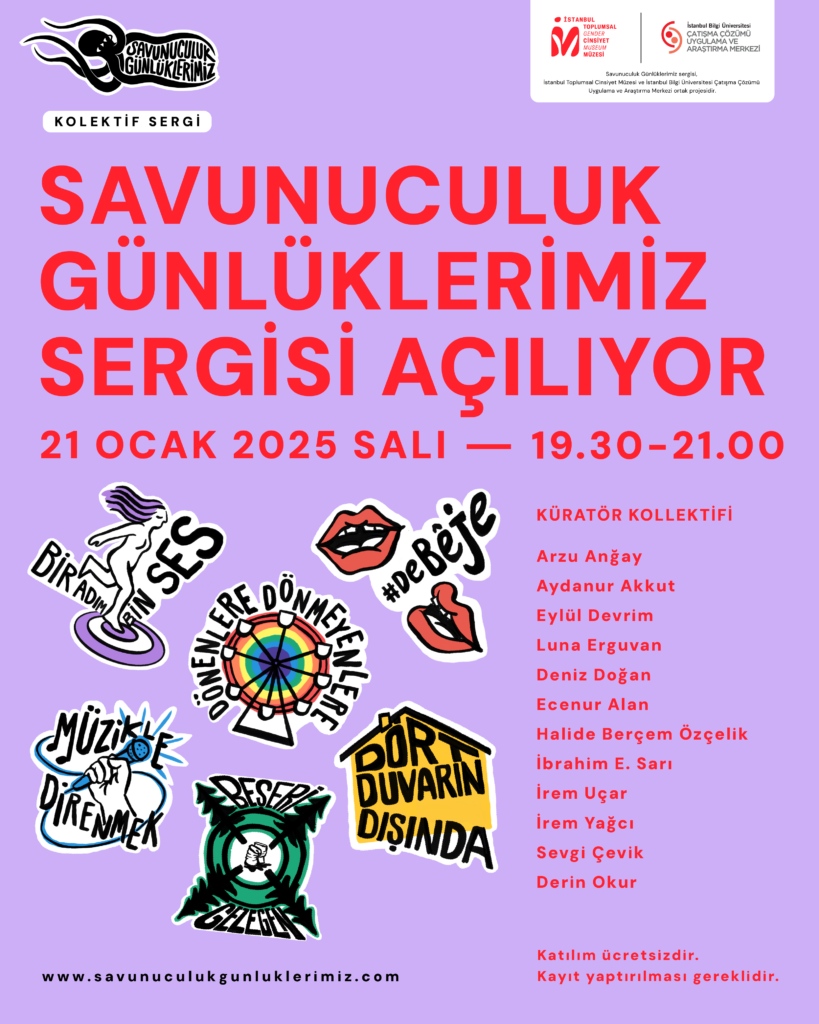

The museum’s latest exhibition, Our Advocacy Diaries (Savunuculuk Günlüklerimiz), was developed around the question, “How can young people be active in museums for political advocacy?” In collaboration with Istanbul Bilgi University’s Center for Conflict Resolution Studies and Application, young people aged 18-25 from various regions of Turkey explored issues affecting their quality of life. They created a series of exhibitions as a form of advocacy. Under the umbrella title of Our Advocacy Diaries, topics ranged from “Fair, safe, and dignified housing for all!” to uncovering the history of women’s struggles in music, women’s rights magazines, and International Women’s Day protest campaigns. One exhibition was designed to campaign for the mother tongues spoken in Turkey, another to celebrate LGBTQI+ activists, and yet another to critically examine human-centered perspectives on environmental protection.

Among the exhibition halls of Our Advocacy Diaries, the #DeBeje #DeBeje (#SpeakUp // #HaydiSöyle) Hall was curated by Ecenur Alan and Halide Berçem Özçelik. I met with Ecenur and Halide to discuss their exhibition and their first curatorial experience.

What is the content of your #DeBeje (#SpeakUp) exhibition?

Halide Berçem Özçelik: Our exhibition is shaped around the mother tongues spoken in Turkey and feminist social media campaigns. The exhibition consists of two sections. In the They Speak (Anlatiyorlar) section, we display feminist social media campaigns that deeply affected us and that we believe deserve greater recognition. These campaigns offer an opportunity to experience solidarity. The We Speak (Anlatiyoruz) section, on the other hand, is designed around the question: “How many mother tongues are spoken in Turkey?”

What was the most surprising information you encountered while researching mother tongues in Turkey?

Halide Berçem Özçelik: What surprised and affected me the most was the 1965 population census document. While I assumed that mother tongues in Turkey had always been invisible and largely unknown, I discovered that 60 years ago, the state had officially documented them. In the 1965 census, people were asked which language they spoke most frequently besides Turkish, and these languages were recorded in official documents. Contrary to what I thought, Turkey’s multilingual structure was actually quite visible at that time.

Ecenur Alan: The most surprising fact for me was the rapid disappearance of mother tongues in Turkey. Looking at the 1965 census, we see that some languages have almost entirely vanished in less than 100 years. Only a very small number of people, mostly from older generations, still speak them. And when those individuals pass away, the language—and with it, an entire culture and collective memory—disappears completely.

Your exhibition includes interactive elements. Can you introduce them?

Ecenur Alan: Of course. One of the most important parts of our exhibition is the Stories (Hikayeler) section. If you have experienced discrimination, hate crimes, or injustice due to your mother tongue—or if someone close to you has experienced such an incident and has given consent to share their story—you can submit it through the “Share Your Story” (Hikayelerini Paylas) section on the We Speak (Anlatiyoruz) page.

Submitted stories will be displayed in the Stories section and will become part of our campaign. Additionally, we have launched a multilingual social media campaign under the hashtag #DeBeje (#SpeakUp // #HaydiSöyle) to increase the visibility of mother tongues spoken in Turkey.

You can share your story in any language on your social media accounts using the hashtag #DeBeje. You can also print and distribute our campaign stickers in your area. We appreciate everyone’s participation in advance!

What are your observations on discrimination based on native language? What should be done to combat it?

Halide Berçem Özçelik: One of my key observations is how quickly Turkey’s multilingual structure has been forgotten, and how older generations experience the most discrimination. The 1965 census showed that many people spoke their mother tongues at home. While preparing stickers for our #DeBeje campaign, I realized how difficult it was to find people who still speak certain languages. For instance, I struggled to find someone who spoke Laz language. Eventually, I found a senior court clerk in my city who helped with our Laz-language sticker. He told me that he was the only person in his family who still spoke Laz. The same happened with Georgian—I had to ask a 50-year-old acquaintance for help. These are just two examples, but many of the languages recorded in 1965 are now forgotten, except for Kurdish and Arabic. Our goal with this exhibition is to expand the space where these languages can still be spoken. By making the issue more visible and open to discussion, we can inspire younger generations who have forgotten or never learned their mother tongues.

Ecenur Alan: Language is more than just words—it carries ways of thinking, social memory, and emotions. Losing a language means losing a part of identity. The process accelerates due to pressures, migration, and urbanization. To keep a language alive, it must be integrated into daily life—into education, arts, science, and public spaces. People should have the opportunity to exist publicly in their native languages.

What is the relationship between multilingualism and social solidarity?

Halide Berçem Özçelik: If we preserve Turkey’s multilingual structure through social solidarity, it could strengthen our society. Multilingualism means diverse identities, cultures, and heritage. It fosters inclusivity, respect, and empathy. With this exhibition, we not only reject the power dynamics imposed by monolingualism but also aim to enhance social empathy.

What would you like to say about the #DeBeje social media campaign?

Halide Berçem Özçelik: With this campaign, we stand against all hate speech and discrimination—not only against mother tongues but also against women, LGBTQI+ people, and people of different ethnic backgrounds. We believe the campaign will grow and transform, standing against the hatred spread through social media.

Ecenur Alan: When creating #DeBeje, we were inspired by our own lived experiences. We had stories to tell. But we were also influenced by the feminist social media campaigns displayed in the They Speak section of our exhibition. These campaigns highlighted gender-based discrimination and violence worldwide, and many grew into global movements. For example, the #HappyToBleed movement raised awareness about menstrual stigma in India and led to widespread discussions. We hope that #DeBeje will similarly transcend borders and foster solidarity.

As Berçem says, we take a stand against all forms of discrimination and hate speech by saying #DeBêje, or #HaydiSöyle (“Go ahead, speak up”). The Stories section, which is part of this campaign, is of great importance in demonstrating this stance. My own story is also included here. What I shared about my grandmother is my deepest truth and sorrow. And I know that I am not the only one who has experienced this. That’s why I invite everyone to share their own stories. We are not alone; we are not invisible. We exist, and we are here. Our stories are our truth.

Among the examples you selected for the “Anlatıyorlar” exhibition hall, which feminist campaign impacted you the most?

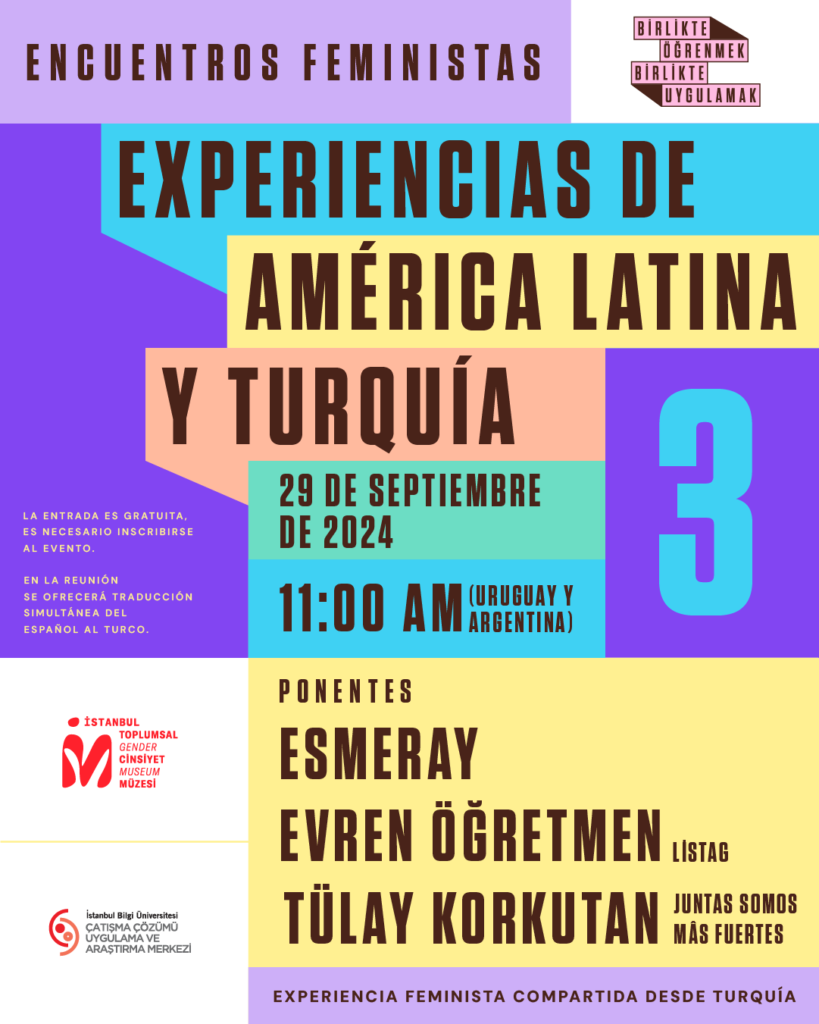

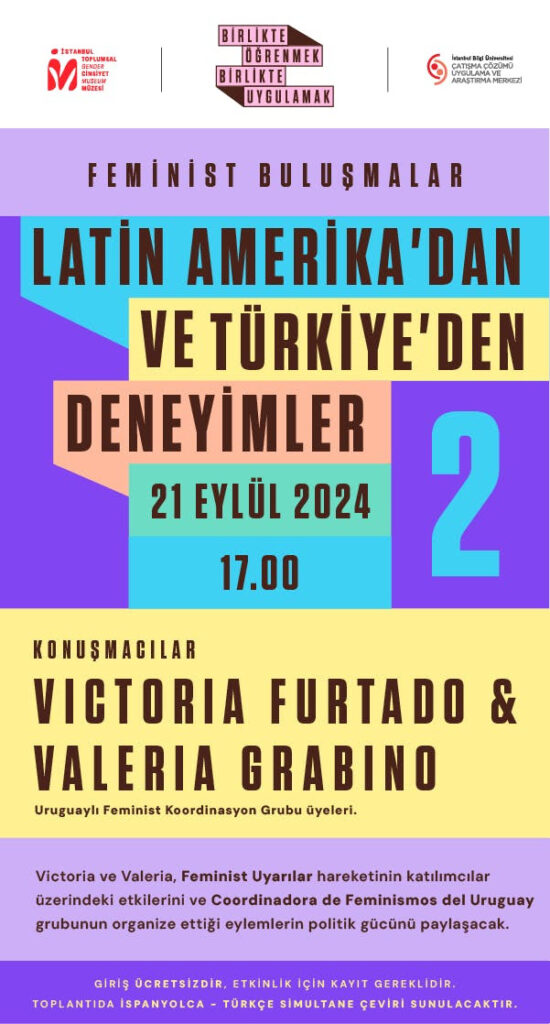

Halide Berçem Özçelik: The movement that influenced me the most was Ni Una Menos. Seeing a campaign that started solely on social media grow into a mass movement that continues to this day was the biggest inspiration for creating our own campaign. Moreover, this campaign was not confined to the country where it started—it spread to other countries as well. The fact that women in Argentina won the right to abortion as a result of this movement made me recognize, once again, the power of social media.

Ecenur Alan: Each of these campaigns is incredibly important and meaningful. It’s truly difficult to choose just one. However, if I had to pick, the campaign that impacted me the most was #sendeanlat (“You tell your story too”). After Özgecan Aslan was murdered, thousands of people began sharing their experiences of harassment and sexual assault on social media using the #sendeanlat hashtag, expressing their thoughts and emotions on the issue. I was 14 years old when Özgecan was killed, and this event deeply shook me. That summer, I had a place to go that was about a 30-minute walk from my father’s workplace. There was also a minibus that followed the same route, but my father strictly warned me never to take it. Even in broad daylight, on a busy street, a short ride of just a few minutes was considered risky. I knew exactly why my father had given me that warning. In fact, even if he hadn’t said anything, the sight of a minibus was frightening to me. Even now, being the last passenger on a bus makes me uneasy. Because we know that no space we occupy is ever truly safe. The #sendeanlat campaign makes the reasons for this insecurity visible in concrete terms, backed by data.

What was the most challenging or thought-provoking aspect of preparing the exhibition in the ‘DeBeje’ hall of the Our Advocacy Diaries exhibition?

Halide Berçem Özçelik: The most challenging aspect of preparing this exhibition was that the issue we were advocating for is one of the politically sensitive topics of today. I could only express what I wanted to say within the limits of what is currently discussable. Beyond restricting my own statements, we also had to respond to certain submissions from visitors who shared their experiences in the Stories section of our exhibition. This project was not just about me and Ece—it carried the responsibility of our visitors and even our fellow curators.

Ecenur Alan: I completely agree with Berçem. Throughout this process, we were in constant communication with each other, revising our initial drafts multiple times. We wanted to create something inclusive, something that truly conveyed a message and made an impact, but we also didn’t want to present it from a detached, privileged perspective. Another challenge was finding stories to feature. The issue we aimed to make visible was one that carried real and deep wounds for people. Expressing, sharing, and making these experiences accessible in such a public space was a daunting prospect for many. And this hesitation was entirely understandable. Fear or the possibility of backlash often silenced people. However, it is precisely to break this silence and show that we are not alone that we say #DeBêje.

______________________

This article was originally published on BIANET on February 21, 2015, to mark International Mother Language Day.

Source: Bianet.org